Portrait of Raoul Hausmann by Marthe Prévot, c.1965. Photo: courtesy of Galerie Hervé Bize

For our purposes, the most important artistic discovery of the 20th century occurred in the summer of 1918, during a vacation on the Baltic Sea. There, the Dada artists and lovers Raoul Hausmann and Hannah Höch were struck by a composite lithograph of Prussian soldiers with photographs of local men’s heads pasted on. The discovery “was like a thunderbolt”, said Hausmann, and the couple returned to Berlin to pioneer the photomontage.

Often repeated and likely apocryphal, the story contains elements that would go on to inspire various 20th-century subcultures. Beyond the formal gambit of cut-up and collage, there is the appropriation of non-art or vernacular imagery, the alchemy of kitsch into high culture, and, perhaps most importantly, the role of chance. Had Hausmann and Höch traveled elsewhere, who knows what might have been different.

Chance connections are at the heart of Hervé Bize and Nicole Klagsbrun’s joint presentation at Independent 20th Century: a freewheeling group show of Dada, Beat Generation assemblage, conceptualism, and abstraction that turns on influence, collaboration, friendship, and romance. It is a fitting project for two dealers whose respective galleries have championed the art world’s outsiders, exploring everything from the occult to street art. Here, they present a selection of artists who could each be considered a liminal presence, widening the lens to reveal a network of thrilling communities.

Dada did not last, and nor did Hausmann and Höch, but the cut-up endured. Its suturing of text and image was an ideal vehicle to critique both commodity culture and the political aggression of the period, and to this day it remains a visual synonym of the movement. Post-Dada, Hausmann fled Nazi Germany to Ibiza, then Prague, Paris, and finally Limoges. His artistic practice was similarly peripatetic, embracing photography while returning to oil paintings, alongside drawings and collages. Always a singular artist, he became a kind of elder statesman to younger artists such as Jasper Johns and George Maciunas, who viewed Hausmann’s work, and Dada in general, as a progenitor of Fluxus.

Raoul Hausmann, Untitled, 1970, collage on paper, 48.7 x 30.9 cm. Courtesy of Galerie Hervé Bize

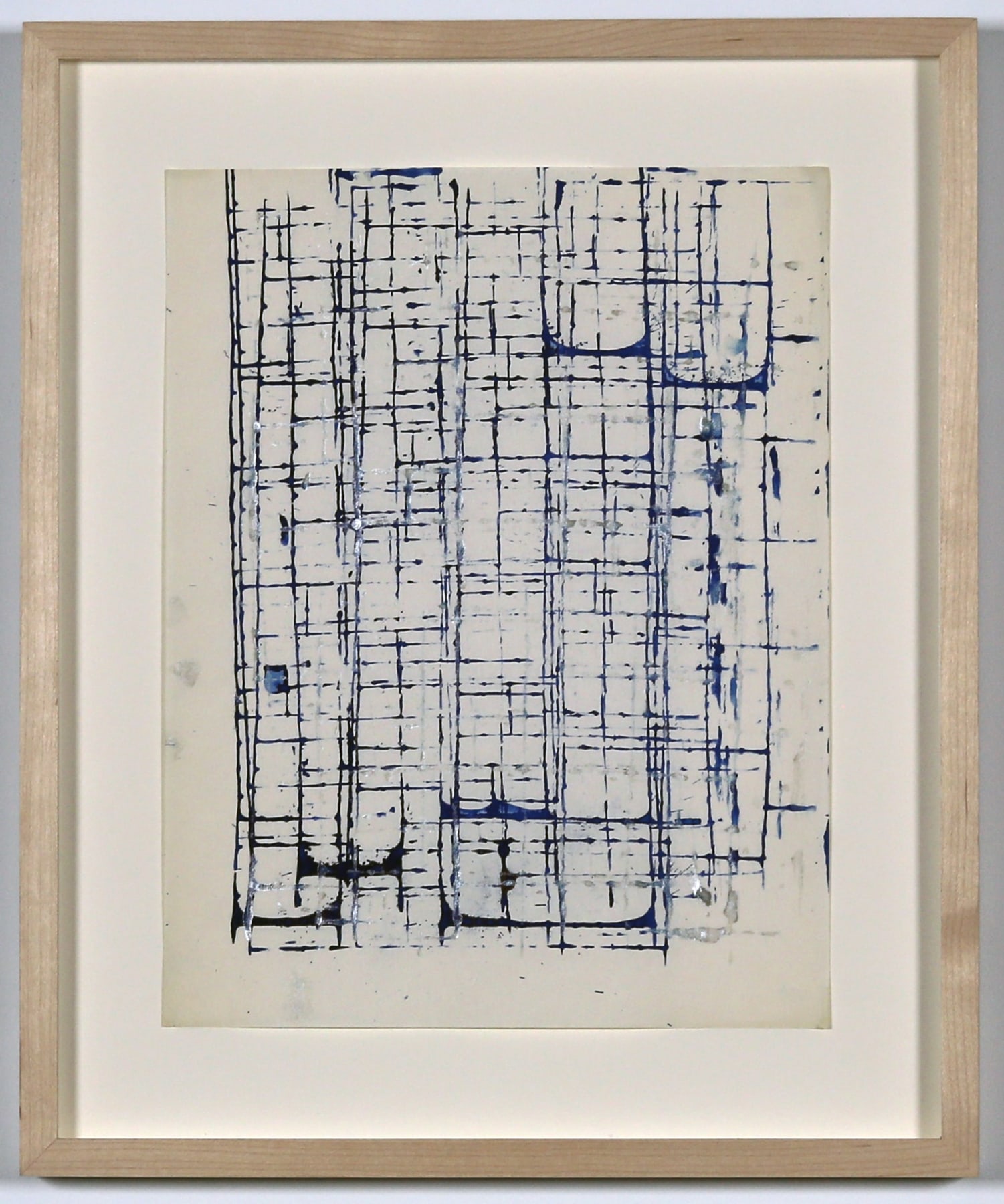

Brion Gysin, Untitled, c. 1962-66, ink on graph paper, 14 x 11.5 inches (frame) 35.6 x 29.2 centimeters 11 x 8.5 inches (image) 27.9 x 21.6 centimeters. Courtesy of Nicole Klagsbrun

Brion Gysin was another cut-up pioneer, born 30 years after Hausmann. In his collaborations with the writer William S. Burroughs, the British-born artist brought the technique into a new generation. Dada’s absurdist collages had shown how scissors and paste could juxtapose, reframe, and shock meaning into revolt. What, these younger artists wondered, could the technique do for language itself? The result, developed by Gysin and Burroughs in Tangier and at the Beat Hotel in Paris, was Burroughs’s notorious 1959 novel Naked Lunch.

Gysin’s untitled 1960s ink drawing, presented by Klagsbrun, further explores the technique and its implications. As part of his experiments with Burroughs, later published in their 1978 book The Third Mind, Gysin would take the edge of an ink roller and grid out a page—cutting up the paper, as well as whatever words happened to have been printed on it. The resulting composition, with its imperfect lines and pools of ink, is not as regimented as the more familiar grids of Minimalism. Its calligraphy has an organic, human, and Eastern quality. It suggests a scaffold with which meaning can be built or deconstructed. And in its automatism, it portends a communing with the subconscious.

John Giorno at the Chelsea Hotel in 1965, photo by Brion Gysin. Courtesy of the John Giorno Foundation

Gysin also collaborated with John Giorno, though that might be putting too light a touch on it. Two decades older than the New York poet and performer, Gysin was Giorno’s mentor, and they were lovers. Over the course of dozens of meditative acid trips in the Chelsea Hotel, their relationship led Giorno to his characteristic mix of Pop and Buddhism. The poem on display, You Can’t Remember Where You Are (rainbow) (1974), speaks to this union: a Day-Glo dip into the well of human consciousness.

Wallace Berman self-portrait, circa 1964. Courtesy of the Estate of Wallace Berman and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles

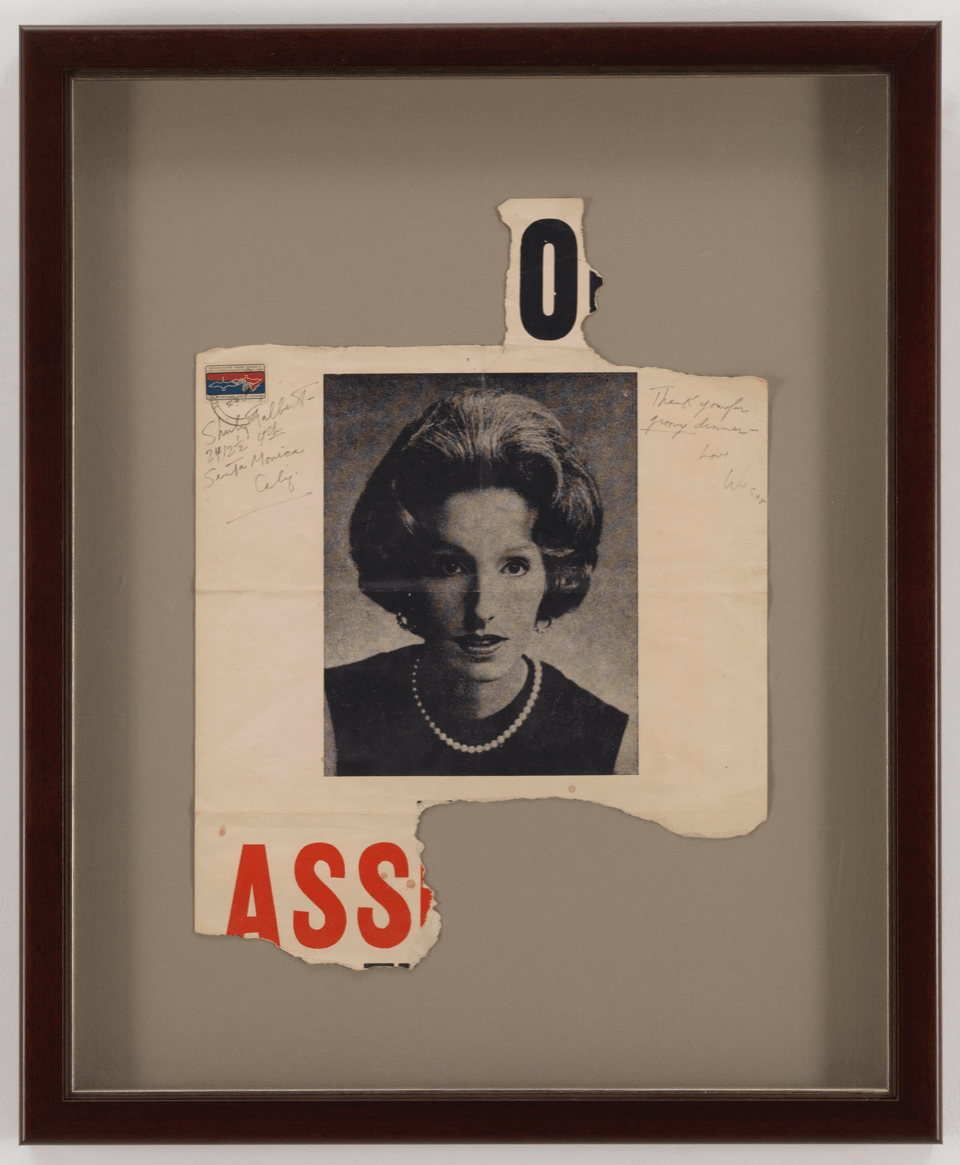

Wallace Berman, Untitled [O/Ass], 1966, newsprint, 27 x 22.5 inches (framed), 68.6 x 57.2 centimeters, 19 x 14 inches (image), 48.3 x 35.6 centimeters. Courtesy of Nicole Klagsbrun

Meanwhile, on the West Coast, another group of artists were charting their own path of discovery. Since the 1930s, California had been a destination for the European avant-garde, with figures like Theodor Adorno, Bertolt Brecht, and Arnold Schoenberg escaping Nazi Germany for sunshine and Hollywood. Add to that mix the literature of Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, jazz, and mind-altering substances, and you can begin to approximate the ingredient list that fueled artists who were interested both in pop culture’s technologies of reproduction and in mystic explorations of the self.

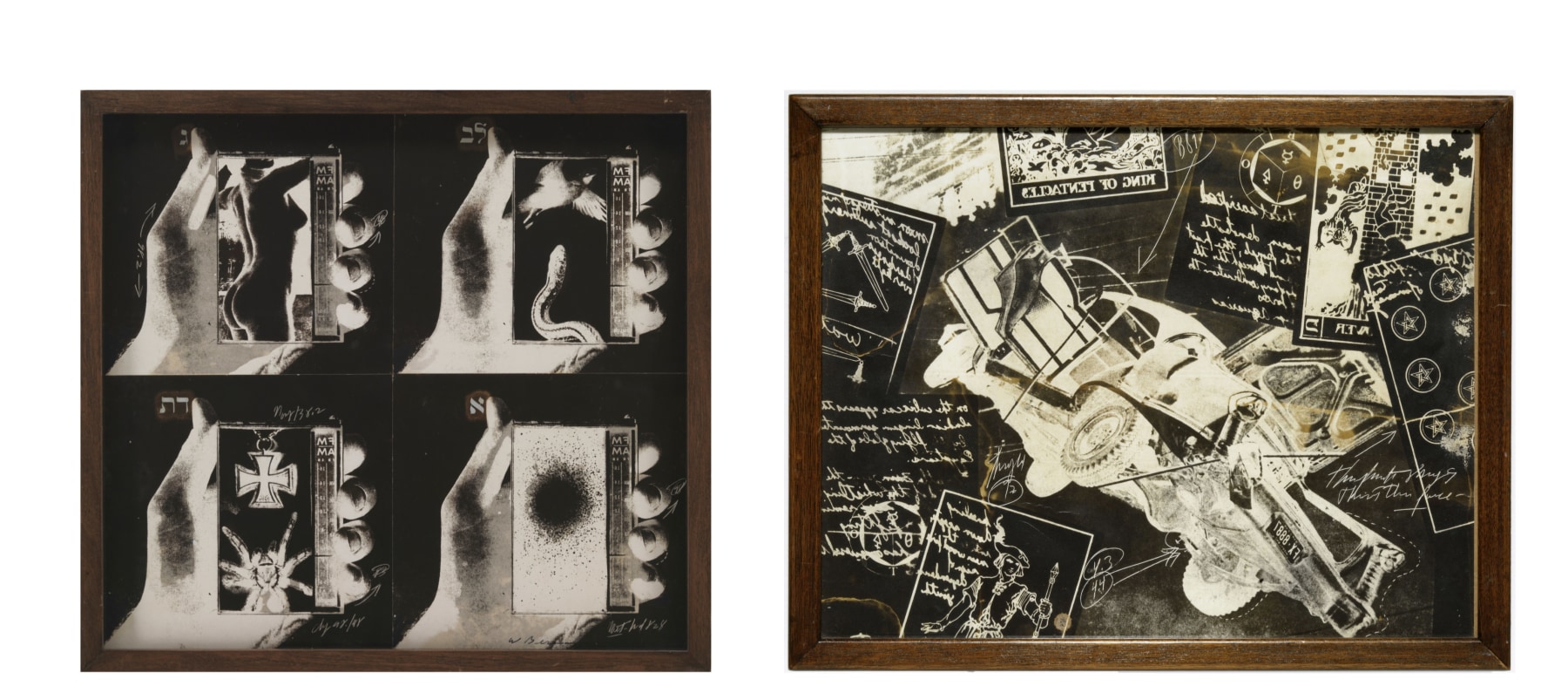

Chief among them were Wallace Berman and George Herms, whose bricolage of images and materials inverted the suburban cheer of Baby Boomer culture. This negative view is clearly embodied in Berman’s Verifax collages. Using negatives from the early Kodak copy machine, Berman created photographic images that shock both in their rebuke of realistic likeness, and their subversive content. An Iron Cross with a tarantula, and a car careening into space. This last piece, Untitled (Airborne Car with Tarot Cards) (1976), made months before Berman was killed by a drunk driver, particularly disturbs in its prescience. Alongside the two 1970s Verifax works, an earlier collage, with a woman’s portrait bearing the word ass, belies a darker approach to assemblage art, one closer to the vitriol of the Dadaists than to Pop’s playfulness.

(L) Wallace Berman, Untitled, 1970, 4-image Verifax negative collage 14 x 13 inches, 35.6 x 33 centimeters. Courtesy of Nicole Klagsbrun (R) Wallace Berman, Untitled (Airborne Car with Tarot Cards), 1976, Verifax collage, negative image 8.25 x 10.5 inches, 21 x 26.7 cm. Courtesy of Nicole Klagsbrun

George Herms, Solar Powered Herms Light, 1988, assemblage, 23 x 17 x 14 inches. Courtesy of Nicole Klagsbrun

From a material perspective, Berman’s assemblage finds an echo in Herms’s Solar Powered Herms Light (1988), in which a discarded briefcase and scraps of decorative lighting are brought together into a new form. Herms’s works speak to the cycle of accumulation and degradation at the heart of consumer culture, as well as the possibility for anything to be given new life. It’s the cut-up meets the junk shop.

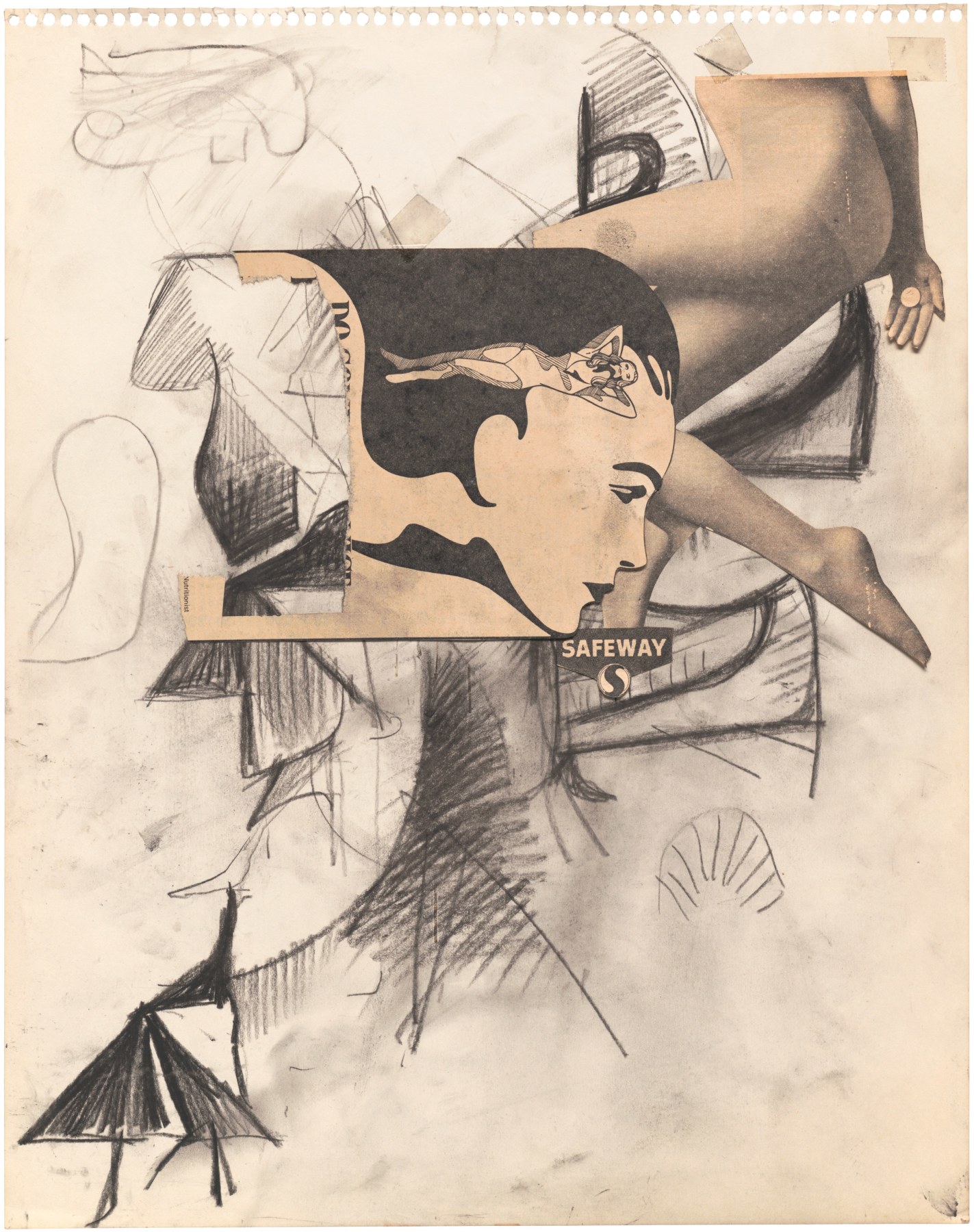

Jay DeFeo, Untitled, 1979. Graphite and charcoal with collage (newspaper cut-outs) on paper, 14 x 11 1/16 inches (35.6 x 28.1 cm). © 2022 The Jay DeFeo Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

If Berman’s collages accumulate images and Herms’s sculptures do it with objects, the Bay Area artist Jay DeFeo was pushing the method into monumental proportions. Her one-ton, eleven-feet-high painting The Rose (1958-66) would not fit in the fair booth (it is in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art), but she is represented by two works on paper whose use of found materials—photographs, game boards, newsprint pin-ups—also points back to Hausmann, Höch, and Weimar Berlin.

This is not to say that the Beat Generation were simply rehashing Dada’s cut-up aesthetic. Coursing through the practices of these California figures was a dark mysticism, in which modern art’s earlier interest in the unconscious dipped further into the mind’s recesses, pulling out visionary and magical images. Nowhere was this more present than in the work of Marjorie Cameron, known simply as Cameron. A follower of Aleister Crowley who influenced Berman and Herms, Cameron blurred the occult and Surrealism in her life and work, delving into astrology, hallucination, and blood rituals.

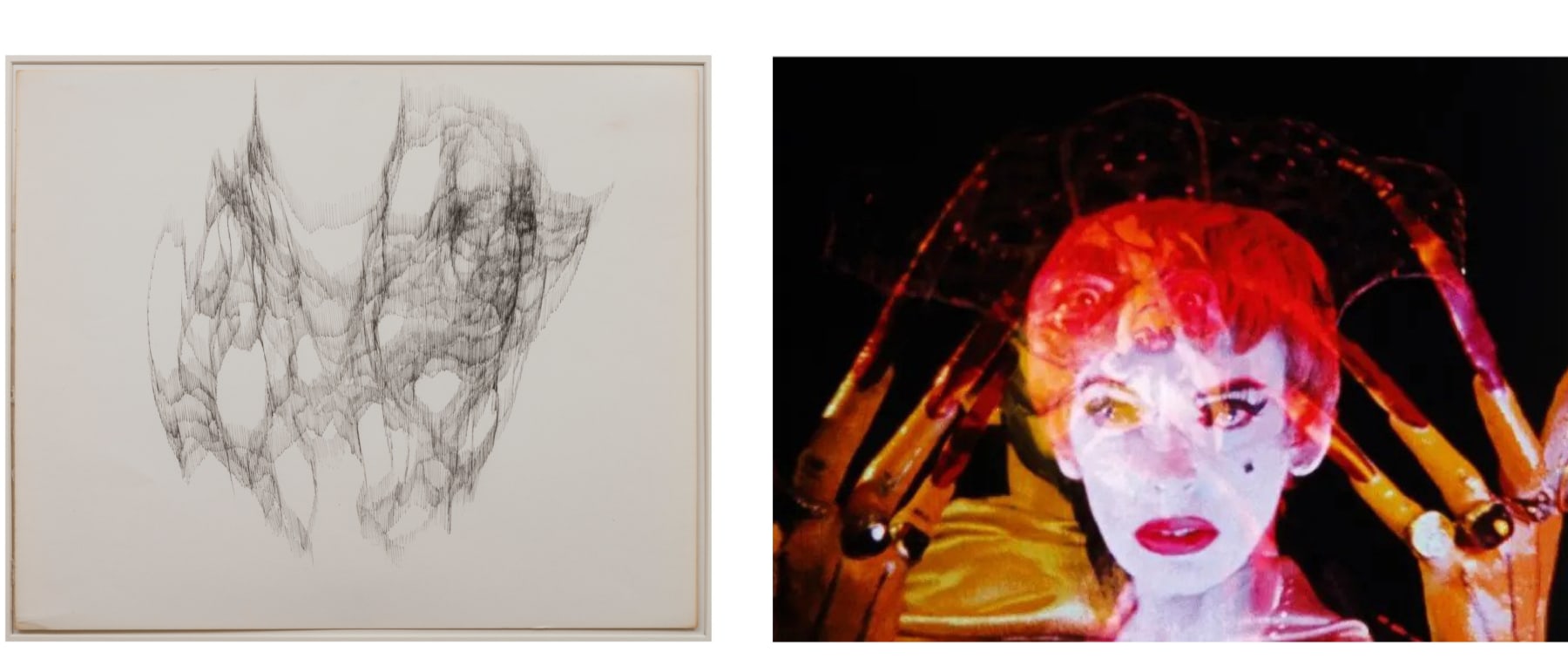

(L) Cameron, Pluto Transiting the Twelfth House, 1978-86, ink on paper, 14.5 x 17.5 inches. Courtesy of Nicole Klagsbrun (R) Still from Kenneth Anger’s 1954 film Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome. Photo: Kenneth Anger, courtesy of Nicole Klagsbrun and the Cameron Parsons Foundation

Raymond Hains, La grille, 1948, silver print, 9.45 x 7.09 inches (image) 24 x 18 cm, 19.69 x 15.75 inches (frame) 50 x 40 cm. Courtesy of Nicole Klagsbrun

The pair of drawings on display, from her Pluto Transiting the Twelfth House series (1978-86), are hauntingly beautiful—an Aurora Borealis of the mind. There is a clear connection back to Brion Gysin, not only in their delicate linework but in their sense of communing, of following an inner voice or spirit. Their aesthetic restraint can also be traced elsewhere, to another group of artists back in Europe who were pushing away from the establishment, liberating art from the object, and inventing new rules to the game.

While assemblage experimented with what could be added into an artwork, a number of French postwar artists were considering what could be taken away. This minimalist impulse was first explored by Raymond Hains, whose 1948 photograph La grille captured light passing through fluted glass to create a slanted grid—one that could be architectural, but is almost totally abstract. In so doing, he foreshadowed the cool distillation of geometric form embraced by America’s Minimalists a generation later.

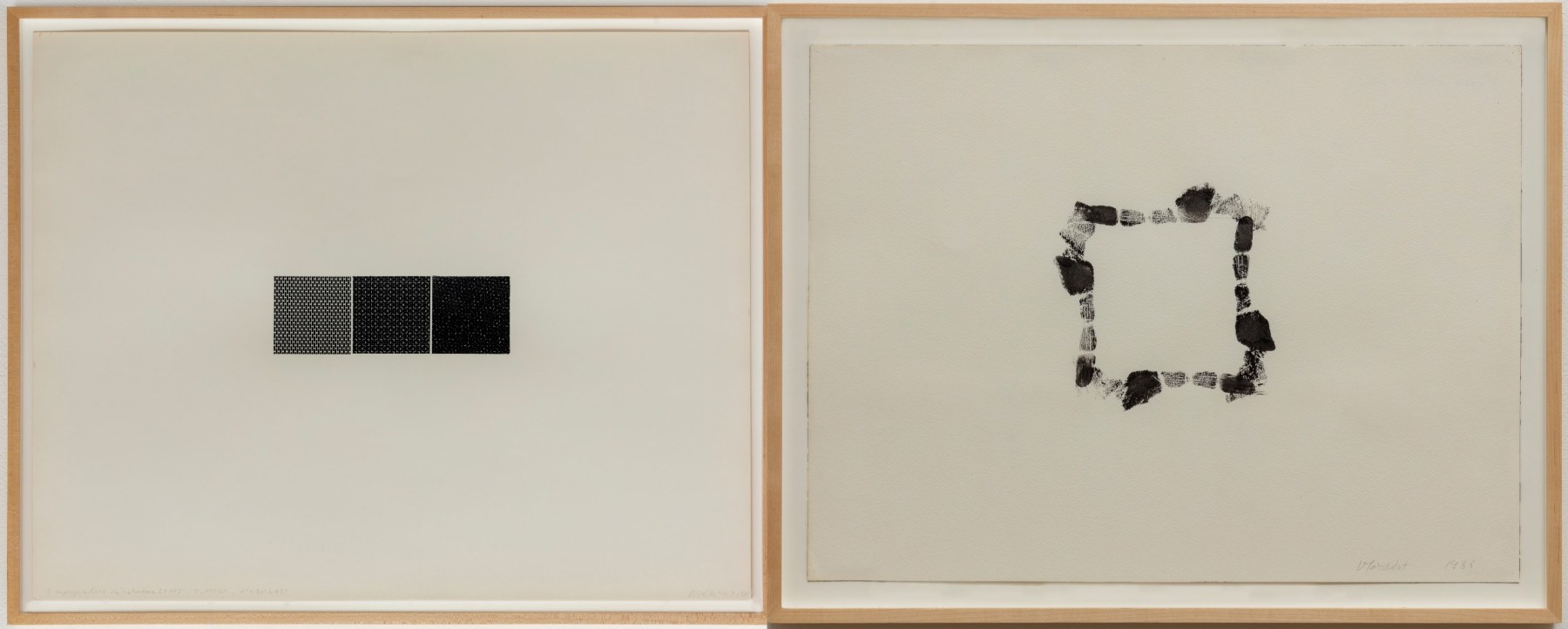

(L) François Morellet, 3 superpositions 0°, 0° + 90°, 0° + 90° + 45°, 1978, collage (Letratone LT 163) on paper, 58.4 x 74 cm (23 x 29.1 inches) Framed: 63.4 x 78.7 cm (24.9 x 30.9 inches). Courtesy of Galerie Hervé Bize and Estate Morellet (R) François Morellet, Figure hâtive n° 3, 1986, acrylic paint and graphite on paper, 46 x 61 cm (18.1 x 24 inches) Framed: 52.7 x 67.6 cm (20.7 x 26.6 inches). Courtesy of Galerie Hervé Bize and Estate Morellet

The same is true of François Morellet, whose virtuosically refined paintings and sculptures coincided with, and often predated, the innovations of artists like Frank Stella, Sol LeWitt, and Dan Flavin. Morellet was a central figure in the development of geometric abstraction and interactive art in Europe, co-founding the kinetic and optical art collective Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV) in 1960. But he held his own production at arm’s length.

For Morellet, the idea behind the artwork was what mattered. After 1960, he left the execution of his paintings to his assistants. But he continued to produce drawings himself, and the examples on view at Independent 20th Century communicate the pleasure he took in creating them: the results are quirky, intimate, charged with ideas. Except for a retrospective in 1991, Morellet’s works on paper have rarely been exhibited. The artist felt that to frame them would be to constrain them, telling Hervé Bize in 2014: “It is as if I was putting back in prison works which had been freed.” The gallerist persuaded him that the pieces could be presented in such a way as to reveal, without hindering, their essential systems.

The idea of freeing the work—and the implication that traditional cultural structures, including the gallery system, are a type of jail—also drove the nomadic practice of André Cadere, who undertook a series of city walks with his signature multicolored wooden bars during the 1970s. Cadere described the project, which straddled the line between performance and sculpture, as “unlimited painting”. From Kassel, Germany, to Paris, to Lower Manhattan, he sought to liberate art from its socially imposed confines.

The solitary figure moving through the city conjures up all types of images: loner, eccentric, shaman. Incorrect terms, to be sure, but similar to the ones that have been leveled at all of the boundary-pushing artists discussed above. Iconoclasts and outsiders in their time, their ideas have become increasingly relevant ever since.

Hunter Braithwaite is a writer, editor, and consultant based in New York. He was the founding editor of Affidavit and the Miami Rail, and has written about art for numerous publications, including Artforum, BOMB, Modern Painters, The Paris Review Daily, and The White Review. He received his MFA in fiction from New York University.